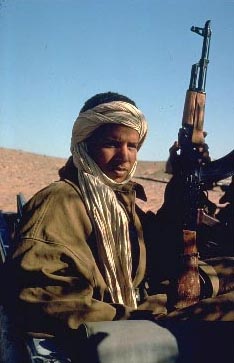

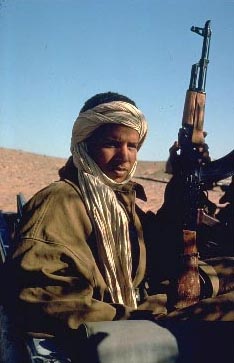

POLISARIO FIGHTER. If international promises remain unkept, then despite the difficulties, Sahrawis may rise again.

POLISARIO FIGHTER. If international promises remain unkept, then despite the difficulties, Sahrawis may rise again. WITH continuing struggles in the Middle East and the mass killing and suffering in Sudan, it's some time since events west of the Sahara made it into our news media, but maybe that is about to change.

In the south-western corner of Algeria, around

Tindouf, some 100,000 refugees from Western Sahara live in camps. Just like the Palestinians,

Sahrawis dream of freedom and a return to their homeland, and the generation that has grown up knowing only exile still keeps that dream, and the will to fight for it, alive.

At the end of February the movement that has led the

Sahrawi struggle for national independence,

POLISARIO, celebrated the thirty-first anniversary of its proclamation of a government, the

Saharan Arab Democratic Republic.

I remember thirty years ago, going along to a cafe near

Paddington station to meet a pleasant and quiet spoken young guy, who wanted to tell me and my left-wing paper's readers about his people's struggle in Western Sahara. The region had seen the departure of Spanish colonial rule, only for people's expectations of freedom to be disappointed when Moroccan troops entered the country from the north, and in alliance with them, Mauritanian forces moved in from the south.

There had been an

infigenous freedom movement,

Harakat Tahrir, inspired by anti-colonial struggles across the Maghreb in the late 1950s, which led to Algerian independence in 1962. Though this first movement was crushed by the Spanish rulers in 1970, three years later in May 1973 a band of patriots attacked a small colonial fort, and

POLISARIO, the

Frente Popular para la

Liberación de Saguia el-

Hamra y

Río de Oro, was born.

A 1975 UN mission reported that

POLISARIO had unrivalled popular support in the country. But that same year, the Spanish government made a secret deal with Morocco and Mauritania, under which they could step into the colonial occupiers' shoes. On October 16, 1976, the International Court of Justice at the Hague rejected Moroccan and Mauritanian claims to Spanish Sahara, and called for a referendum on self-determination. That has still to take place.

Though Mauritania eventually dropped its claims and withdrew from the territory,

Moroccon forces, backed by Western supplies and Saudi money, continued trying to suppress the

Sahrawis, while

POLISARIO fought back using its popular support and knowledge of the terrain, and aided for a time with weapons from Algeria and Libya. Meanwhile thousands of

Sahrawis fled into the Algerian refugee camps. After 15 years, having dragged on into stalemate, the war ended in a UN-brokered ceasefire in 1991. Once again the

Sahrawis were promised a referendum on independence, supported by the UN secretary general no less.

Another sixteen years, thousands remain in exile, those left behind are being rendered a minority by

Morrocanisation, and with Moroccan troops still ruling Western Sahara, the ceremonies to mark the anniversary of the republic did not take place in

Laayoune, the country's declared capital, but in the small outpost of

Tifariti near the Algerian border.

According to Jacob

Mundy, writing in Middle East Report Online, "If it seems that the peace process in Western Sahara has moved at a glacial pace, that is because it has actually moved backwards. From 1981 to 1999, negotiations were premised on a pledge by the late King

Hassan II that Morocco would allow and respect a referendum on independence. By the terms of the UN Settlement Plan that underpinned the ceasefire, the UN mission in Western Sahara (

MINURSO) tried in vain from 1991 to 1999 to stage such a plebiscite. The referendum seemed to acquire a new lease on life in 1997 when then newly appointed Secretary-General

Kofi Annan designated former US Secretary of State James Baker as his personal envoy to Western Sahara. But the referendum, and Morocco’s support for it, essentially died with King

Hassan in 1999."

Paradoxically, it was King

Mohammed VI’s dismissal of Interior Minister

Driss Basri, seen as signalling a break with past repression in Morocco, that removed the prospect of a referendum, as Jacob

Mundy explains. "Part of

Basri’s job under

Hassan, besides torturing and 'disappearing' dissidents, was to fix elections. If he could get over 90 percent of Moroccans to approve a constitution, he could surely induce 120,000

Sahrawis to choose integration into Morocco. By mid-1999, however, it was clear that

Basri’s tactic -- peopling the voter rolls with Moroccans posing as

Sahrawis -- had failed".

Meanwhile, the UN Security Council had seen itself forced to intervene in East

Timor, after a referendum on independence there was drowned in

bood by the Indonesian army and its sponsored gangs of thugs. It feared the same kind of thing might happen in Western Sahara. UN secretary general

Kofi Annanreported in 2000 that several arguments had been raised against continuing with the 1991 plan, and that “even assuming that a referendum were held…if the result were not to be recognized and accepted by one party, it is worth noting that no enforcement mechanism is envisioned by the settlement plan, nor is one likely to be proposed, calling for the use of military means to effect enforcement.” In other words, if Morocco lost the referendum and decided to ignore the result, there was nothing you could do about it.

Mundy, a

Ph.D student at

Exeter University, notes that

Polisario has come under pressure to accept a scheme proposed by James Baker, and apparently endorsed by King Mohammad, according to which Morocco would grant limited autonomy to local Saharan leaders. But he believes the

Sahrawi leaders will come under opposite pressure from their own people, particularly the young, to renew the struggle. (This apparently despite the probability that besides facing US opposition, they would nowadays be unlikely to get Libyan or Algerian support).

" The great success of

POLISARIO’s founding fathers is that they fostered a political movement that is now self-sustaining and, more importantly, self-motivating. But that is part of the problem. Having reared younger

Sahrawis on the slogan “All the homeland or martyrdom,” the

POLISARIO elite is now hostage to its own rhetoric. It has become a practical and logical impossibility for

POLISARIO’s leadership to compromise the fundamental goal of independence. To do so would mean that they are no longer

POLISARIO; and if they were no longer

POLISARIO, then their constituents -- Western Saharan nationalists -- would have no further use for them.

"On October 31, 2006, the Security Council passed Resolution 1720, 'reaffirming its commitment to assist the parties to achieve a just, lasting and mutually acceptable political solution, which provides for the self-determination of the people of Western Sahara.' In other words, and despite the nod to “self-determination,” nothing will be forced upon Morocco. The Security Council, here guided by Morocco’s key allies France and the United States, wants a “mutually acceptable” agreement between

POLISARIO and Morocco that is negotiated and implemented voluntarily. Out of one side of its mouth, the Security Council calls for a vote on independence; out of the other side, it tells

POLISARIO it will not compel such a poll. By clear implication, the Security Council’s conditions for peace in Western Sahara demand that self-determination be sacrificed'.

"Though

POLISARIO is feeling international pressure to compromise, it is feeling more internal pressure to fight back -- literally. The same cold logic that gives Morocco comfort generates frustration among Western Saharan nationalists. The refugees, in particular, are keenly aware that their cause is boxed into a corner.

"Tensions have already boiled over in Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara, where there were unprecedented demonstrations in May 2005. Unlike previous manifestations of

Sahrawi discontent, these protests openly called for independence, rather than more rights or more jobs. Since then, the rallies have degenerated into daily minor confrontations between

Sahrawi youths and Moroccan security forces. The trajectory of the unrest, known to

Sahrawis as the May intifada, is not apparent, in part because of a near blackout of international coverage imposed by Morocco. But

Sahrawis are being pushed to contemplate more drastic measures. For the time being, the youths are heeding the calls for non-violence coming from the older activists. Should Moroccan repression escalate, however,

POLISARIO could be unable -- or unwilling -- to stop elements of its military stationed along the 1991 armistice line from attempting to draw Moroccan troops’ fire.

"

POLISARIO is caught between two antagonistic pressures, autonomy and intifada. How the movement navigates these pressures in the coming months will determine the future of Western Sahara.

"Routine Moroccan quashing of a small demonstration in

Laayoune provided the spark that ignited the

Sahrawi intifada in May 2005. Yet the underlying causes of the non-violent independence movement come from 30 years of living as a divided population, suffering violent repression and being ignored by the international community and, on top of all that,

socio-economic marginalization -- the “

Moroccanization” of Western Sahara. The demonstrations of May 2005 came as a shock not only to most observers of the conflict, but to many

Sahrawi nationalists as well.

"The red, green, white and black colors of

POLISARIO, once rarely seen in Moroccan-controlled Western Sahara, have become the symbol of

Sahrawi resistance, whether spray-painted onto school walls -- in the shape of the

POLISARIO flag -- or braided into the hair of young girls.

"Though not lacking in militancy, the intifada has not gathered sufficient momentum to impel a major rethinking of policy either in the Moroccan palace or at the Security Council. Coercion, of course, plays a large role. A debilitating number of key

Sahrawi activists, young and old, languish in Moroccan jails, occasionally teetering on the edge of death after prolonged hunger strikes. But Moroccan security men keep the Western Sahara story out of the global media by refraining from massive displays of force and confining themselves to more intimate and targeted acts of violence. These extrajudicial policing measures are aimed squarely at known activists, as well as their friends and family. The website of the

Sahrawi Association of Victims of Grave Violations of Human Rights Committed by the Moroccan State is replete with documented examples of police brutality and “confessions” obtained under severe duress. Another spark could set Western Saharan towns ablaze".

http://www.merip.org/mero/mero031607.htmlLabels: Africa, Maghreb

IN FULL SAIL for profit, whatever war is on the horizon? Rising like Sinbad's dream, the world's tallest (330m) and it's said, finest hotel, the Burj al Arab, is symbol of Dubai's properity.

IN FULL SAIL for profit, whatever war is on the horizon? Rising like Sinbad's dream, the world's tallest (330m) and it's said, finest hotel, the Burj al Arab, is symbol of Dubai's properity.